Fire Emblem: Awakening has a lot to say about women.

Fire Emblem, Womanhood, and the End of the Inevitable

It walks out the gate with a comfortable, well-done war story. War is bad, and the people who like war are bad. Good men are fighting for their country. Good women are doing just about everything. Helping their country, yes. Leading armies. Leading rebellions. Living as healers, warriors, princessess, and dragons. Fire Emblem has always played its cards straight: Women are a part of this war story. They're a part of every war story, of every story, period.

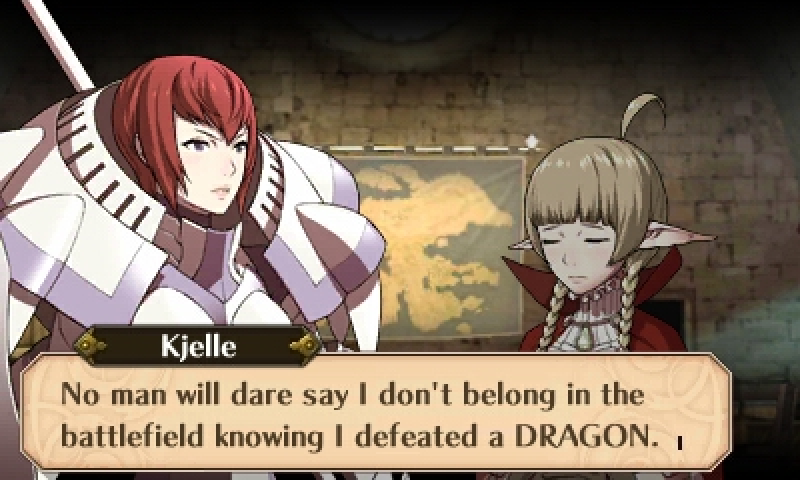

In the mechanics language of Fire Emblem, there's nothing particularly special about women. There's nothing really wrong with them, either. There's female-exclusive classes— Pegasus Knight, Troubadour— and a few male-exclusive ones, too. Units care more about skills and classes than stereotypes. The stereotypes are still there, though. Awakening hasn't stripped sexism away, it's taken it into account. Written into the story, it puts women at the center of a struggle between themselves and the expectations being placed on them.

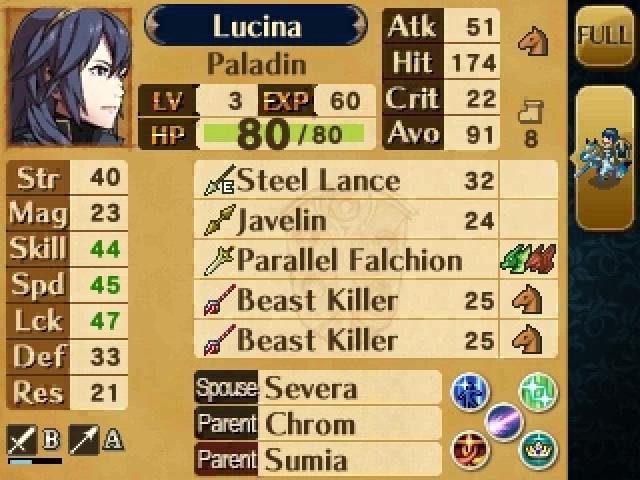

The game plays these cards with a wink and a nudge. It's not exactly tongue-in-cheek, but the story is working with you, not against you. It justifies and exemplefies the women in its setting, plays with the roles of masculinity and femininity. Lucina, as a perfect example, struggles with her role as Chrom's daughter. She spends the first half of the game hidden in a faux masculine shell, playing off of Chrom's expectations to keep her identity a secret. She's desperate. She needs Chrom to see her as an ally first, a daughter second, and a woman third.

Characters like Sumia, on the other hand, struggle to find their place in a sea of kings and castles. Being a soldier means finding the right king and settling into the right castle. It means living up to expectations or betraying them in a good way. And so it's important for every woman in the game to create a role for themselves— not a female role in the traditional sense, but a role that represents their contribution to the war. A Pegasus Knight. A Troubadour. A class, a function.

Then, time travel gets involved, and these functions change.

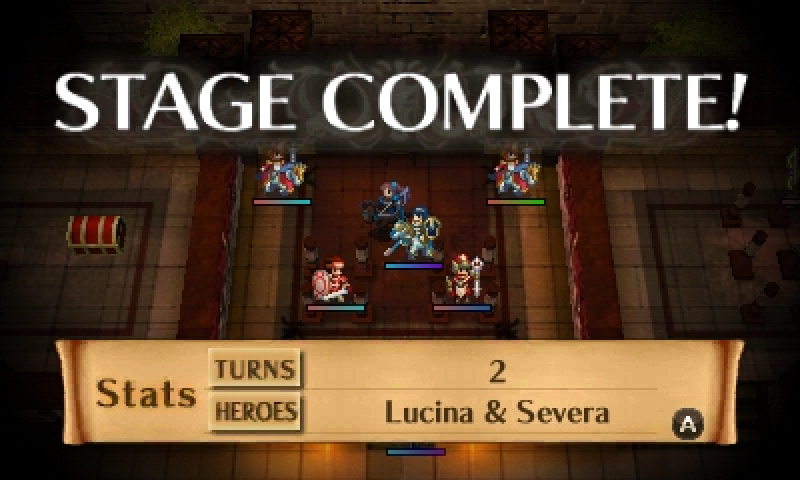

Sumia is Lucina's mother— in my version of the game, at least. Because of the demands of the story, Lucina needs to have a mother, but the specifics don't matter very much. The mechanics and the narrative start to drift apart from each other, here. Lucina's mother, whoever she is, is stripped of her narrative role, and her mechanical role takes over.

It's Chapter 11. Chrom needs to have a kid right now.

Who is she going to be?

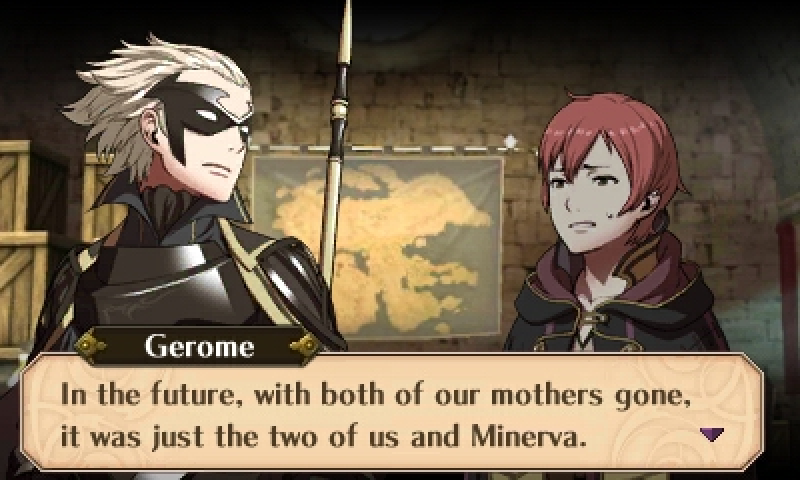

This is Awakening's biggest misstep. The future, by nature of the story, has already come to pass. The children have been born, the stakes have been raised, and the survivors have looped back to the beginning to try to save the future— but the game can't just account for that. The mechanics are written and preserved facing forward, as the player plays. Lucina's future past, as the game describes it, is altered to match the mother that the player— or the game— has chosen for her. It falls back onto the language of numbers to try to describe fleeting concepts: Childhood, parentage, authority, lineage. The role of the mother in the story, her class, is imprinted onto her child. The child loses their mother, and returns from the future to keep fighting the war.

For just one moment, as the game passes hands from the first act to the second: Every woman, a mother. Every mother, a martyr.

The key to understanding Awakening's relationship with women is to follow through on the core of the story. Lucina, child of the future, is coming back to change the course of history. This isn't a game about predestination. Womanhood implies motherhood, but it doesn't guarantee it. Female characters who don't start relationships in the present are excused completely from having children, of even letting you know that their future children might exist. They're allowed to focus on the war— to fulfill a role as a woman without fulfilling a "woman's role."

Here, the conflict between the game's story and the game's systems really takes off. Mechanics demand consistency; development demands simplicity. The story wants to explain that this isn't a game about women being forced to have children, but that's willfully ignoring the structure of the game's design. Women are entirely tied to their children, and vice-versa. Their name, their stats, their class, their role as a human being in the war, it all boils down to being a mother or being a child. And this further strips women of their agency in the game's own narrative.

Women are a very powerful force in Awakening. The future children are, by all accounts, much stronger than either of their parents. It's worth recruiting them. It's worth using them— raising them, as the player— to replace their parents' role in the war. Galeforce, the game's de-facto most powerful skill, is a skill that only women can learn... unless it's one of the future children, who get guaranteed skills from their mom. It puts men and women on a level playing field, but only as two halves of the same whole. A woman is simply one set of possibilities that must be combined to make a child. Her existence inside and outside of the war is an expression of motherhood. Of predestination.

A woman starts a relationship and her child is already manifested into the future, written into the story like they had always existed, to be picked up by the player and written a second time into a soldier. This relationship, the one between the character and the player, is always being strained. I like Sumia as a warrior, not as a mother. I like Chrom as a king, not as a father. And the game can nod and wink as much as it wants, but it can't repair that relationship for me. All of the children are baked into the timeline from the start, hiding in the game's data. The game only waits for me to move my hand so that it can put those pieces into place.

I'm not trying to scorn Awakening. It's grappling with this problem as much as I am— the contradiction of writing a story about changing the future, through the lens of a game that relies on predicting it. Womanhood and motherhood, biological essentialism, it's asphyxiating. It drags the pacing and the tone of the game to a desperate halt. Here are oh-so-many missions, here are so many more units to take care of. How does Robin, the player, fit the finality of the future into the war of the present?

Awakening does have an answer to this. In the game's ending, Robin finally rejects the framing of predestination and argues that the characters are destined to find their own future, separate from the one that already exists— that the women of this story aren't doomed to a biological role. The characters are allowed to grow out of their role as soldiers; the women to grow out of (or into) their role as a mother.

There's something here, a commentary that being a mother and being a soldier are both just roles. Like a class, an archetype, the women in Awakening lose their role as the player loses access to them. Their lack of agency is a reflection of the player's ability to influence the game. The player, acting through the game's systems, enforces the structure of motherhood onto these women.

It's an uncomfortable role to play.

I want to put a pin in Awakening because its messaging creates a conversation without a conclusion. It presents one idea, contradicts it, and then tries to fill that gap with a third idea— storytelling flying by the seat of its pants. And I want to defend it, because conversations without conclusions tend to turn into vent posts: Reviewing games by how uncomfortable they are.

Well, Fire Emblem: Awaking is uncomfortable, and that's not an accident. It presents an uncomfortable situation, an open conversation, and asks the player to engage with it at face value.

It is, beyond a shadow of a doubt, disturbing that women could be "predestined" to give birth, that men in the same situation wouldn't have to deal with the same reality and responsibility of that future, that children only exist to be a product of their parents or of their circumstances, but that's not something that we can assign blame to. Fire Emblem didn't create those ideas; it presented them.

In reality, no future is set in stone. No one person is doomed to be a mother, a martyr, or a soldier. That, of all things, should be the takeaway: Just because someone is expected to be something doesn't mean that they're going to be. Roles can be rejected, or changed.

And at its core, that's the story that Awakening is trying to tell.